SCARF Model

What is it?

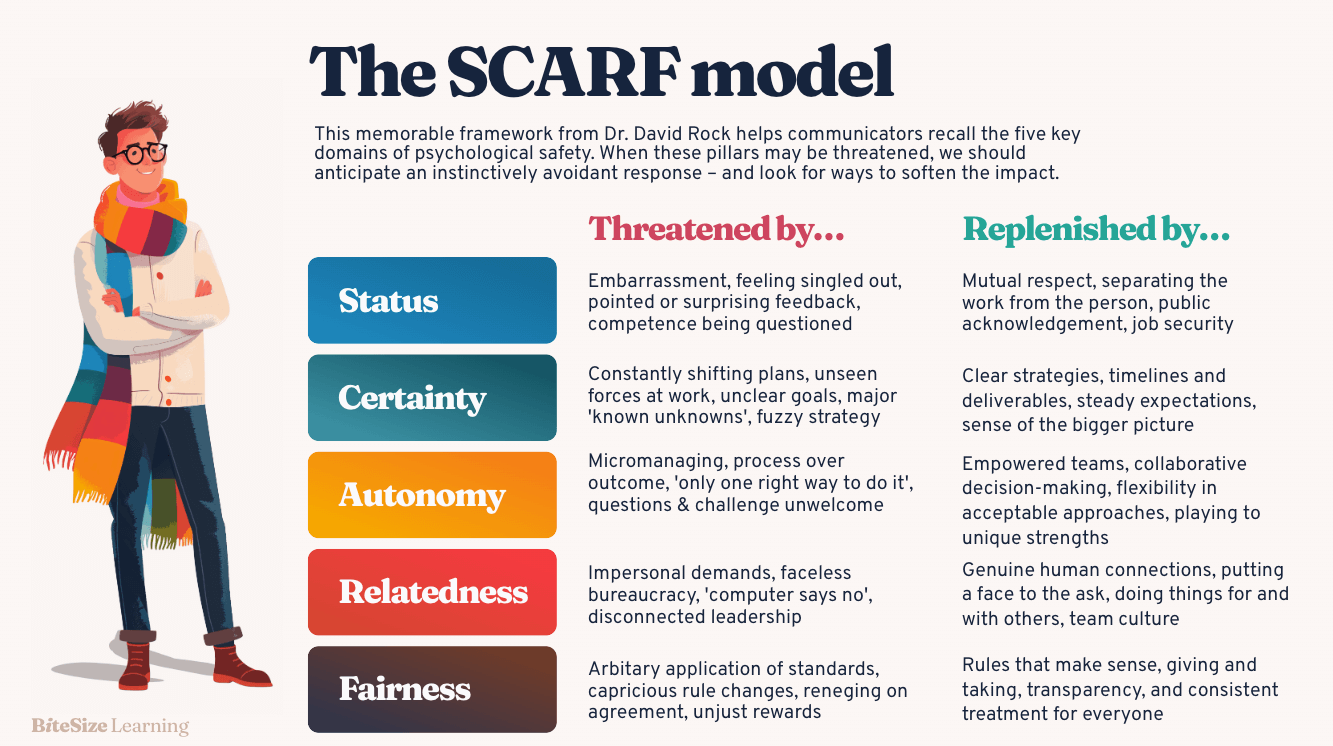

The SCARF Model (by David Rock) identifies five social drivers—Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness, and Fairness—that influence motivation and behavior.

The SCARF Model explains what makes people feel good or bad in social situations. It’s based on five key things our brain cares about:

1. Status (Feeling Important)

People like to feel valued and respected.

- Example: If your boss praises your work in front of others, you feel good. If they criticize you publicly, you feel bad.

2. Certainty (Knowing What to Expect)

Uncertainty makes us anxious; predictability feels safe.

- Example: If your manager clearly tells you what to do, you feel secure. If they keep changing plans, you feel stressed.

3. Autonomy (Having Control)

We like to have choices and control over our actions.

- Example: If you get to decide how to do your work, you feel motivated. If you’re micromanaged, you feel frustrated.

4. Relatedness (Feeling Connected)

We want to belong and trust others.

- Example: If your team welcomes you warmly, you feel included. If they ignore you, you feel isolated.

5. Fairness (Being Treated Justly)

Unfairness triggers a negative reaction.

- Example: If a coworker gets a promotion they don’t deserve, you feel upset. If rewards are given fairly, you feel satisfied.

By understanding these triggers, we can improve teamwork, leadership, and relationships!

The SCARF Model: A Neuroscientific Approach to Social Motivation

Introduction

The SCARF Model, developed by David Rock (2008), is a neuroscience-based framework that explains human social behavior by identifying five key domains that influence motivation and performance. This model aligns with research in psychology, behavioral economics, and neuroscience, particularly in relation to reward and threat responses in the brain. Understanding SCARF helps leaders, managers, and organizations improve communication, engagement, and team dynamics.

The Five Domains of the SCARF Model

1. Status: The Drive for Social Hierarchy

Humans are deeply sensitive to social rank and recognition, as status affects survival from an evolutionary perspective. Studies in social comparison theory (Festinger, 1954) show that we constantly evaluate ourselves relative to others.

- Neuroscience Link: Activation of the dopaminergic reward system when status is increased (Eisenberger et al., 2003).

- Example: Public recognition at work boosts motivation, while negative feedback in front of peers triggers a threat response.

- Related Principle: Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs (Esteem Needs).

2. Certainty: Predictability Reduces Cognitive Load

The brain is a prediction machine, and uncertainty creates cognitive stress. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for decision-making, is highly sensitive to uncertainty, leading to stress responses (Lupien et al., 2009).

- Neuroscience Link: The amygdala triggers a threat response when uncertainty is high.

- Example: Employees feel anxious when management frequently changes policies without clear communication.

- Related Principle: Cognitive Load Theory (Sweller, 1988) – too much uncertainty increases mental effort.

3. Autonomy: Control Enhances Motivation

Autonomy is crucial for intrinsic motivation, as highlighted in Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985). When people lack control, stress hormones like cortisol increase, reducing cognitive performance.

- Neuroscience Link: Increased activity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex when autonomy is high, associated with reduced stress (Maier & Seligman, 1976).

- Example: Employees perform better when given flexibility in how they complete tasks.

- Related Principle: Locus of Control (Rotter, 1966) – those with an internal locus of control tend to be more resilient.

4. Relatedness: Social Connection as a Survival Mechanism

Human beings are wired for social connection, as seen in studies on oxytocin, a hormone linked to trust and bonding (Zak, 2012). Lack of relatedness leads to social pain, which activates the same neural pathways as physical pain (Eisenberger et al., 2003).

- Neuroscience Link: Activation of the anterior cingulate cortex during social exclusion.

- Example: Remote workers often struggle with a sense of isolation, reducing engagement.

- Related Principle: Social Bond Theory (Hirschi, 1969) – strong connections enhance commitment.

5. Fairness: The Brain’s Built-in Justice System

Unfairness activates the insular cortex, which is also linked to disgust responses. This is why perceived injustice triggers strong emotional reactions (Sanfey et al., 2003).

- Neuroscience Link: The dopaminergic system responds negatively to unfairness, reducing cooperation.

- Example: Employees disengage when they see favoritism in promotions.

- Related Principle: Equity Theory (Adams, 1965) – fairness affects motivation.

References

- Rock, D. (2008). "SCARF: A Brain-Based Model for Collaborating with and Influencing Others." NeuroLeadership Journal.

- Eisenberger, N. et al. (2003). "Does Rejection Hurt? An fMRI Study of Social Exclusion." Science, 302(5643), 290-292.

- Deci, E. & Ryan, R. (1985). "Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior." Springer.

- Festinger, L. (1954). "A Theory of Social Comparison Processes." Human Relations, 7(2), 117-140.

- Sanfey, A. et al. (2003). "The Neural Basis of Economic Decision-Making in the Ultimatum Game." Science, 300(5626), 1755-1758.

- Lupien, S. et al. (2009). "The Effects of Stress Throughout the Lifespan on the Brain, Behavior, and Cognition." Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 434-445.